Sweeping, adjective—Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism In 1975 Australian photographer Sue Ford (1943–2009) documented the American art critic, curator and activist Lucy Lippard’s visit to Australia. The trip was intended to furnish Lippard’s understanding of the place for emotion, intimacy and agency in art with regards to the women’s liberation movement abroad.2 8 November 2014This (book) is a kind of experiment in inversion. It is based on a wager: that subjectivity can be thought, in its richness and diversity, in terms quite other than those implied by various dualisms.1

- extending or performed in a long, continuous curve

- wide in range or effect

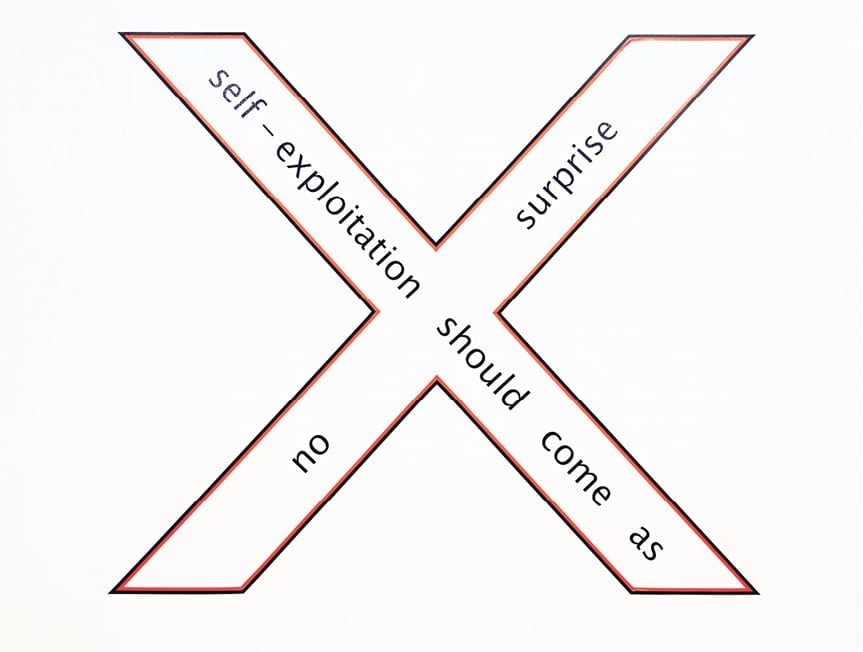

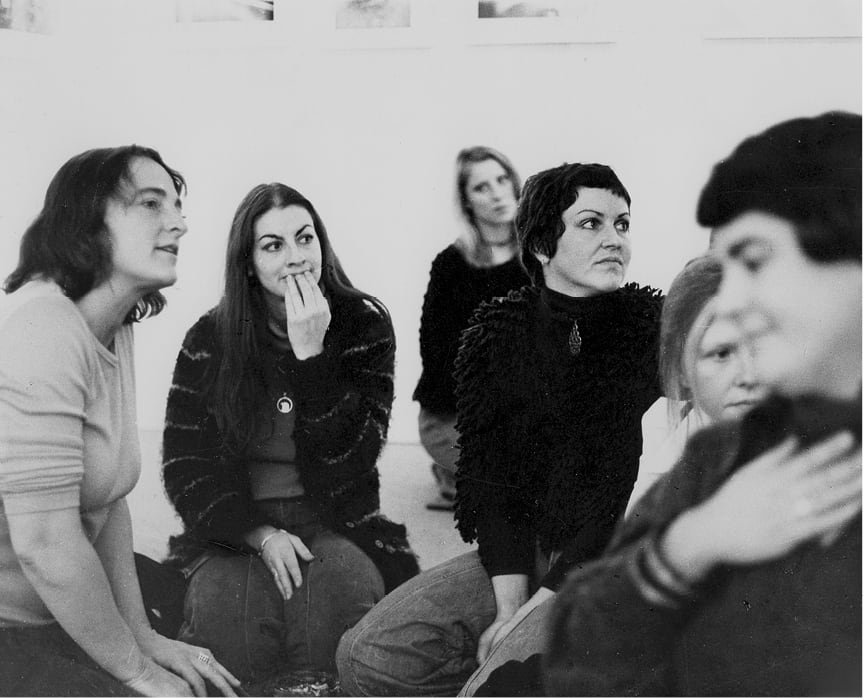

Dear Sue, I recently visited your retrospective at the National Gallery of Victoria. As a bookend to your being the first photographer to hold a solo exhibition there in 1974, it was an important moment of circuitry to have been privy to. You would have been really proud to see the show. Whilst looking at your photographs and video pieces from the women’s movement era of the 1970s, one image in particular occurred to me above all others. It was No Title (Lucy Lippard at Ewing Gallery) 1975. Either we never worked on this image during our time together on your archive, or it never resonated with me at the time. Granted I was young and whilst I wasn’t consciously circumventing or dodging my inevitable feminist coming out, it was not in my awareness to consider these images above any others. Since encountering the amazing work of Lucy Lippard during my time living in North America, this image with all its associated and overlapping histories has a new significance to me now. I have fond memories of sitting in your kitchen on sullen overcast Balaclava days, listening to local indigenous radio and drinking tea. We talked about some of the more sentient points that we had in common, such as Buddhism and art. It’s a shame you’re not around to continue these conversations. I would have so many things to ask you, particularly now since I have recently, finally, come out. With love and admiration, Abbra3In 1957 Ernst Kantorowicz published The King’s Two Bodies: A Study in Mediaeval Political Theology, as referenced in Hito Steyerl’s essay ‘Missing People: Entanglement, Superposition, and Exhumation as Sites of Indeterminacy’.4 In it historian Kantorowicz offers guidance on the arcane mysteries of mediaeval political theology whereby the notion of the king’s two bodies—the body politic and the body natural—is theoretically exhumed. Where the body natural state yielded to mortal signifiers (disease, death and decay), the body politic survived as the immaterial, immortal and spiritual locus of the king long after he had died. Long Live The King! With the idea of the king’s two bodies came the Christian tradition of political theology, giving rise to earlier forms of the nation-state. Fast forward to the twenty-first century and the king’s two bodies offer an appropriate metaphor for a trans-historical induction into the function of constituent, natural bodies in the radical articulation of the political body that we call feminism. In the twenty-first century, the split body—as signifier and signified—appeals acutely to the politics of the layperson (working class, marginalised or oppressed) working against the authority of the king as nation-state. If we delegate the historic task, we find that what was once valued as the corpus mysticum (mystical body) of the common religious order can today be regarded as a symbolic agent of cohesion for a diverse and emblematic feminist body politic. Furthermore, we notice a profound resonance between the image of the mystical body and the variegated and contradictory claims of contemporary feminism, corroborated by the nuanced nature of feminist agency from the body as it is expressed in the world. Almost two decades after Lippard published her paperback Get The Message?: A Decade of Art for Social Change (1984), Ford created her Shadow Portrait series (2002). In these images Ford exhumes the bodies of nineteenth century colonial Australia, replacing them with more esoteric and natural ephemera. These images read almost as quotations from the cover of Get the Message? with its depiction of what appear to be nuns or other appointed women, the background cut away to reveal their figures in brazen pink. In both instances the natural bodies of the legacies of our past shift into new incarnations. What both artists have done by exhuming these historic texts in apropos to the contemporary feminist subject is to consummate a radical act of collective articulation that values historical consciousness and agency. In this regard, these bodies can be considered moving targets which once re-imagined allow for new sites of exchange. Re-Raising Consciousness, a recent exhibition and participatory installation at TCB Art Inc. (13–29 November 2014) sought to revisit some of the methods, philosophies and collective needs garnered by the feminist consciousness-raising groups that originally sprung up in New York in the late 1960s. Curators Fayen d’Evie, Katherine Hattam and Harriet Morgan worked to involve an intergenerational group of artists to construct an exhibition redolent of the kinds of living spaces that mobilised the early affinity groups out onto the streets of the women’s liberation movement. In considering the subtext to Re-Raising Consciousness, the curators have positioned the Re- of the title as both a statement and a call to action. By means of re-enacting a consciousness-raising group—with the assistance of original documentation and its disclaimer as an experimental oratory—a kind of archival performance materialised that was about cognisance with an historical ideation of feminism, whilst cultivating a renewed conversation amongst its present members.

‘The subject does not belong to the world: rather, it is a limit of the world’5 —Ludwig Wittgenstein in Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and FinanceThere are many potential crescendos that occur in conversation between Ann Snitow and Victoria Hattam during a video interview that was conducted for screening within the TCB living room. One of those moments is when Snitow ardently defends the feminist project for its ability to renew itself through intergenerational revivification. By paraphrasing Bulgarian theorist and psychoanalyst Miglena Nikolchina, ‘she thinks that you can’t get around the profound misogyny that buries women’s subjectivity as a subject of history’,6 Snitow reappoints feminism in all its multiplicity as having the ability to pull women’s subjectivity out of the wreckage of this historical smothering. In this way, you could say that Snitow is defending the kind of attitude towards the subject that Wittgenstein avows. With each generation of insurgent women, the subject of women’s emancipation is being pushed to the perceived limits of the known world at any given time. For this reason and others, Snitow is adamant in her belief that feminism will never die; it will simply be taken up by each successive generation in ways relevant to their time. Despite the limiting tendency to frame feminist precincts in the form of waves, there is merit in looking to the proposed fourth wave feminist concerns as it works to cut across lines of race, class and non-binary gender expression. In addition to these claims, the fourth wave is historically unique for the fact of its modus operandi—the internet—working to liberate women’s voices away from the narrow clutches of media dictatorship that fortified previous eras. In order to appreciate the kinds of historic infrastructure that has ushered in the contemporary condition it is important to revisit feminism’s second wave (1960s to early 1980s). One of Lippard’s primary claims in her essay ‘Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s’ concerns the inherent intricacies of the feminist operation: ‘Feminism’s major contribution has been too complex, subversive, and fundamentally political to lend itself to such internecine, hand-to-hand stylistic combat.’7 Due to her reluctance to enumerate names, this text becomes an exercise in spilling forth a vast and broad feminism; one that is venerated for its hard work in rupturing and dismantling a very rigid, singular modernist ethos. Lippard’s use of simile and visual metaphor concerning this claim is vivid and on-point; she illuminates the power of feminist causation within modernism’s evolution as a series of tributaries, flooding and spilling forth from the mainstream flow of modern art and political life. It is here that a kind of theoretical autopsy is performed on the dual corporality of the king’s two bodies, substantiating Steyerl’s claim to the indeterminacy of Kantorowicz’s thought experiment regarding a congealed sovereignty against the image of a decentralised and autonomous feminist subjectivity. As with the archetype of the Roman god Janus, contemporary feminism’s predisposition for rhizomatic growth (horizontally and non-linear as opposed to hierarchical) corroborates its position as a kind of revolving door with one set of eyes always to the past and one to the future. If we consider the contemporary condition as a continuation of the Romantic pursuit of trans-historicism (that is to consider the divided gaze as a mapping device for charting where we are now in relation to our past), we once again return to the task of superimposing; past with present, deceased with living bodies. One effect of applying this historical transparency is to highlight the apparent tensions across the contours of each period, and to further consider the contingencies of the bodies—respectively dead and alive—that Steyerl opens up. In this way, we can argue that the act of re-raising (consciousness) becomes a critical component for reinstating the relevance of the feminist project trans-historically. It is precisely due to a lack of any overarching, agreeable definition of what a feminist subjectivity might look like against its historical image that we can agree at least on its enduring contemporaneity (read: indeterminacy). Returning again to the etymological task, the word feminism can be thought of as a contranym—a word with two or more incongruous and contradictory meanings—as a fundamentally Janian term. As Snitow elsewhere discusses in her work Pages from a Gender Diary: Basic Divisions in Feminism:

We perform subtle psychological and social negotiations about just how gendered we choose to be. This tension—between needing to act as women and needing an identity not overdetermined by our gender—is as old as Western feminism…the specialness of women has this double face…8

We have to make ourselves not as a projected abstract ideal, but out of the shape of here and now… The movement between conception and action, culture and social revolution, is partial, laboured, and painfully slow. But it is the only way we can heave ourselves into the future.10 —Sheila Rowbotham, Woman’s Consciousness, Man’s WorldAbbra Kotlarczyk is a visual artist, writer and art history student at the University of Melbourne.

1. Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, 1994, p. vii.

2. Megan Backhouse, ‘Living in the seventies: exhibition looks back at a different way of looking’, The Age, 21 October 2011.

3. Abbra Kotlarczyk, excerpt from the original text Sweeping Exchanges read by Fayen d’Evie on the occasion of Re-Raising Consciousness at TCB Art Inc. 2014.

4. Hito Steyerl, ‘Missing People: Entanglement, Superposition, and Exhumation as Sites of Indeterminacy’ in The Wretched of the Screen, Sternberg Press, Berlin, 2012, p. 143.

5. Franco ‘Bifo’ Berardi, The Uprising: On Poetry and Finance, Semiotext(e), Los Angeles, 2007, p. 156.

6. Ann Snitow in conversation with Victoria Hattam, 24 & 27 September 2014, New York (Video by Hayley A. Silverman).

7. Lucy R. Lippard, ‘Sweeping Exchanges: The Contribution of Feminism to the Art of the 1970s’, Art Journal, Fall/Winter 1980, New York, pp. 362–365.

8. Ann Snitow, quoted in Maria Elena Buszek, ‘Waving Not Drowning: Thinking about Third Wave Feminism in the U.S.’, published in Make: The Magazine of Women’s Art, no. 86, 1999–2000, pp. 39–40.

9. Maria Elena Buszek, ibid, p. 2.

[^10]: Sheila Rowbotham, Woman’s Consciousness, Man’s World, Penguin, Baltimore, 1973, p. ix.