In some cases, the failure of a work of art can be traced back to inconsistencies between content and form; however, as we see in Matthew Greaves’s exhibition MF at West Space, failing to be coherent in this sense can also be seen as a strategy, if not the actual point. In the exhibition Greaves presents four works adapted from online material found on various men’s rights activist forums, such as ‘MGTOW’ (Men Go Their Own Way) and ‘A Voice For Men’. In each work, Greaves appears to both highlight and undermine the agency of the source material through formal and conceptual strategies that emphasise a broader dialectic of visual contradiction.

In the first instance, Greaves brings together adapted examples of men’s rights paraphernalia in the form of printed and framed T-shirts, while underhandedly subverting their messages through tactics of displacement from centre to periphery. This is exemplified firstly through Greaves’s positioning of the shirts, which appear to have suspiciously fallen from their central place inside the frame. The tactic of displacement is further accentuated by the work’s final location, leaning against the wall rather than fixed to it. The slogans ‘Have you thanked a man today?’ and ‘WORK, it’s what a man gets to do’ correspond to stylised representations of men as heroic soldiers or fatigued workers. The original men’s rights message in this work has undergone manipulation through the adaptation of imagery and by its formal displacement, a tactic that renders the paraphernalia legible but literally looked down upon by the viewer.

Moving instinctively counter-clockwise, the work Untitled (Secrets of the female mind) comprises an audio recording and a wide flat-screen monitor featuring a Caucasian woman communicating in sign language while standing in front of a green screen. For viewers who cannot understand sign language, the perturbing nature of this piece becomes apparent only after putting on the earphones attached to the monitor. Upon doing so, one hears the voice of ‘female thinker’ Suzanne Hindmarsh—whose name I learned after rediscovering the dialogue online. In the recording Hindmarsh speaks of the so-called ‘secrets of the female mind’, citing examples of women’s lack of consciousness and capacity for reason. Similar to the framed T-shirts, Greaves tampers with the agency of the original message, here introducing the visual precursor of silent gesticulation and the insulating capacity of earphones that impose physical limitations on the audio work. In his book Matter and Memory, Henri Bergson explains the phenomenon of the encounter as something intrinsically bound up with and mediated by the sequence of events that precedes it. By constructing a dominant visual precursor to the perplexing experience of the audio, Greaves has made subversive use of technical supports, such as sign language (which functions here as both translation and echo), and earphones (as a censoring mechanism) to undermine the authority of Hindmarsh’s message.

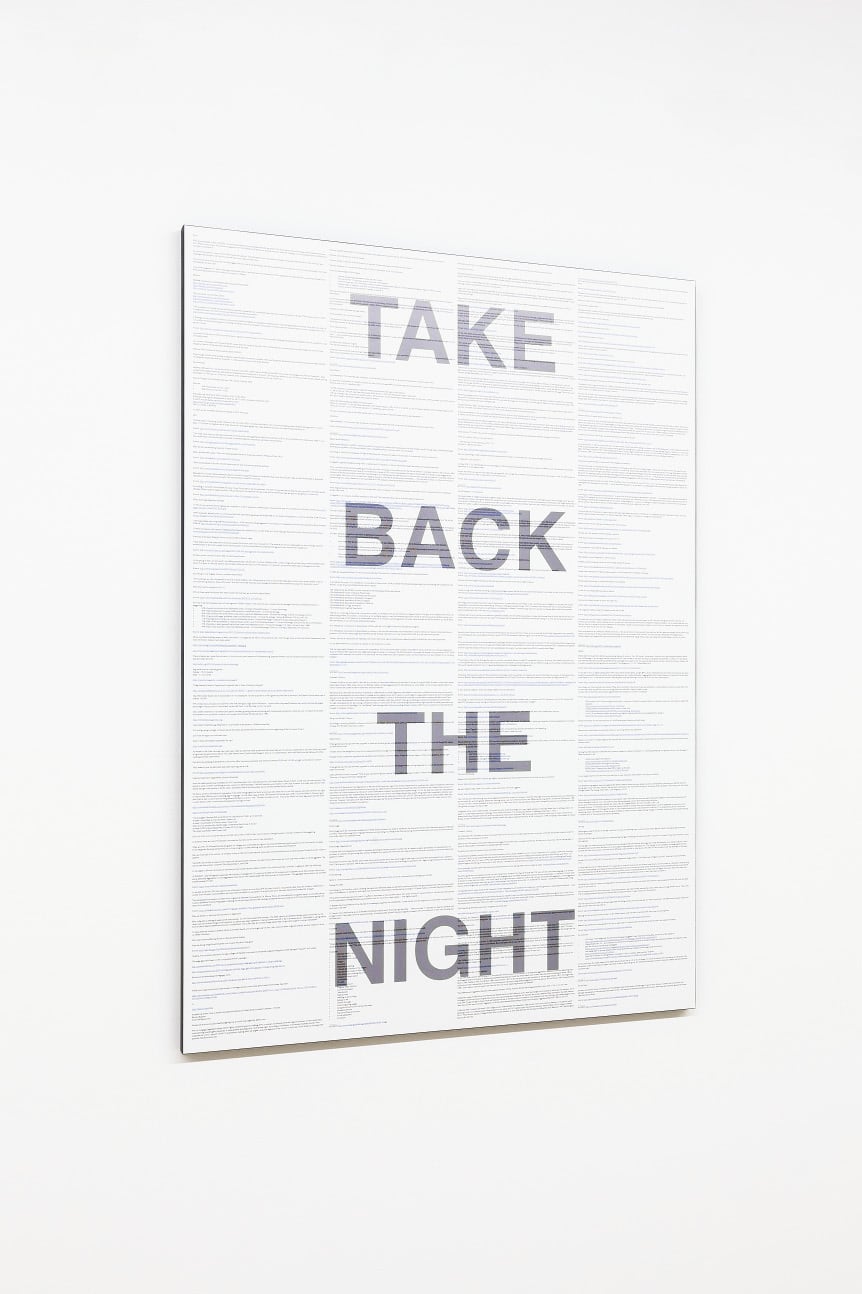

The final and possibly most contentious work in the exhibition is a large mounted poster titled Take Back The Night, which exposes a list of statistics instancing the adversity men face in society and by various government institutions, such as the military, the prison and the family law court. Boldly layered over the top of these statistics is the phrase ‘Take Back the Night’, an international feminist slogan used annually in anti-rape and anti-violence demonstrations since its inauguration in Brussels in 1976. It’s noteworthy to add that since the late 1990s the TBTN march has also included men and has been opened up to new strains of protest against violence more generally. What viewers probably don’t know about this poster is that the bold font on the original source material reads, ‘Are you a happy Feminist?’ which Greaves surreptitiously answers with the new title Take Back The Night. By constructing a sophistic palimpsest of rhetoric, Greaves could be either answering the call for men’s rights or nullifying both sides of the argument. We might ask: does this poster attempt to re-engage historical and liberal feminist strategies in support of equal liberation for men? Or, instead, does it simply point to an aspect of the exhibition that hasn’t yet been spoken: a sense of ambiguity that is perhaps felt most strongly in our response to the exhibition title itself, MF, which could stand for ‘Male Female’ or, alternatively, ‘Mother Fucker’?

Georgina Criddle is a visual artist and research candidate at Monash University.