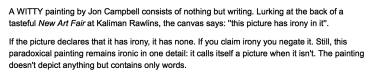

There’s materialism and there’s materialism. Some documents.1

It’s as though this writer is speaking to and on behalf of a public that thinks not-knowing about Adorno, St John of the Cross, Derrida or Lacan is a responsible ignorance. As though to know that double messages could displace and even replace an image or thing is a kind of lack of respect for what-we-all-know as a unified public.^2

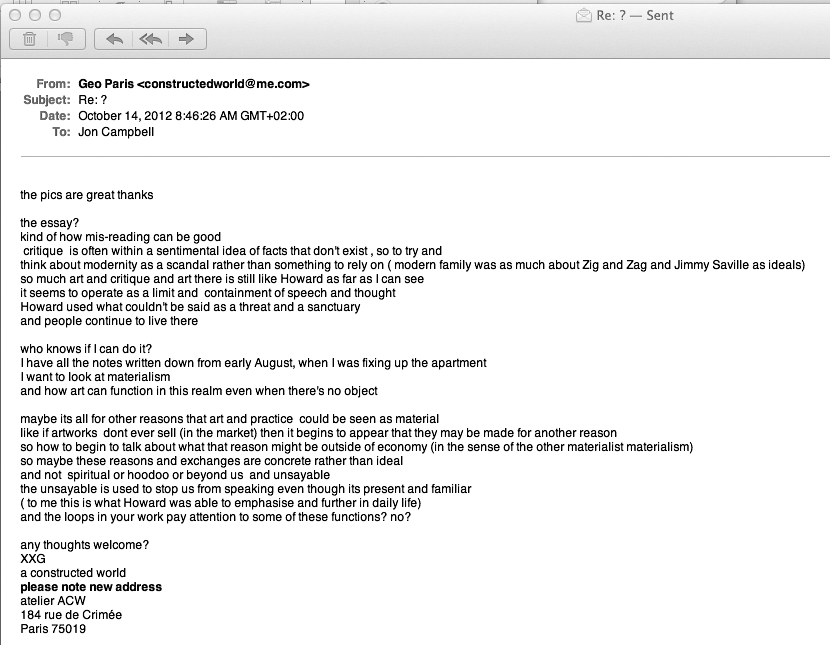

We have reached a kind of upper-class populism, it’s at the crossroads of neo-liberalism and our colonial heritage. It’s a question of access rather than class, like some people have more access to a $13m payout or bonus than others. Being greedy, as always, requires duplicitous and disingenuous acts. We are complicit in ignorance and innocence because they both generate rewards. University students from the best suburbs grow up over a generation impersonating lower class accents. I can’t help but think of my Auntie Joan from Glenroy who said ‘kiddies’, ‘luv’ and ‘yairs’, just what are they saying about her? I’m kind of pissed off on Joan’s behalf: she was provided with a limited repertoire and did quite a lot with it; those with access to the most our society can offer make a living out of making fun of those who didn’t have access to resources. We love to watch those who have-it-all take the piss. Culture has been a social space that is best to rubbish or avoid — somehow it never quite represents our Australian way of life, unless it’s Kath and Kim or Edna.

What can’t we say in our country? Watch the mainstream movie The Falcon and the Snowman from 1985 (directed by John Schlesinger), it’s all about how the CIA deposed the Whitlam government but we choose to see otherwise. What can’t we say in our country? Pauline Hanson was demonised by the educated classes as a racist, yet Gary Foley, as a Marxist, invoked that he identified more with her (who he calls Pauline) than those who villfied her, as though in preference to the relentless liberalism that often guides us against each other.

Not saying about what you know or have learned is rewarded in trumps. It’s like after the interregnum in England between the monarchs (1649-1660), it seems once the sovereign was restored, the whole country chose not to mention the period of revolution and democracy.

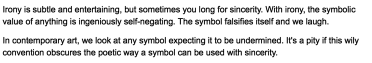

What can’t-be-said begins to be more valued and lauded than what can be uttered. I think I’m repeating myself, I’ve said all this before. Where does what-we-can’t-say lie?

The eternal, the unspeakable and unsayable are well expressed in Joseph Beuys’ documented performance from 1965, How to explain pictures to a dead hare. Beuys incants without saying, a long, silent discourse around a kind of holy purpose of art. He could be a shameful shaman?

There are better and more able people than me to give you, the reader of this text, a definition of Materialism, to-tell-you-what-it-is. Schopenhauer wrote that ‘materialism is the philosophy of the subject who forgets to take account of himself’. Let’s call that herself. For this reason it could also be useful to consider recent efforts in feminist studies to link what has been seen as utterly unsayable, in most periods of history, to materialism. See Samantha Frost’s topological jaunt through Thomas Hobbes’ ideas of sovereignty where she seems to be saying that people (subjects) use fear as means of getting autonomy from those whole rule over them.3 The public are strategically disingenuous as a means of getting-what-they-want or feel they deserve. It seems the constituents understand well those who publicly preach water while secretly drinking wine. They pretend to be more racist, sexist and traditional than what their actual and private actions attest to. A common ‘object of fear’ can certainly increase the sovereignty overall, yet this insincerity and even deceit of different publics also increases the terrain of ways-of-saying and begins to put an end to the idealised, uncomplex behaviours that we are meant to be living in. Or, as John Howard would have it, the behaviours and ideals that were seen to be so good in the past, that we need to get back to now. This is the scandal of modernity and its relation to the unsayable that allowed the Catholic church to rape so many children in the twentieth century.

We rely on and take refuge in the unspeakable rather than accepting that nearly everything is difficult to express or document and we rarely know what is actually going on either individually or collectively. One thing is for sure, it’s possible to use a word like materialism without knowing what it means.

The state-of-nature that Thomas Hobbes so often cautions and warns us about as the ultimate object of fear could in fact be a litany and corollary of all our dense and complex needs, desires and behaviours.

Jon Campbell is ingenious and disingenuous in making ignorance or innocence material. Whitlam spawned a lot of Culture: The Whitlams, The Post_Goughists and more. You think that’s a bad leap? Well that’s what I’m looking for. Gough Whitlam was actually in that second Barry McKenzie film, I think he makes Edna a Dame in it.

The irony is that people in the art world, corporations and governments, govern to govern. By being sincere we make ourselves visible to reify and repeat what-we-already-know, to restate the same tawdry constrictions that more or less prevent us from speaking and saying the unutterable. But let’s get back to irony… Jon Campbell in his earlier works bemoans cover versions, presumably through a desire for something authentic. In what juvenile way could a symbol be actually connected to reality in the first place? That could only be a trick. This could be bad for the market.

Somehow instead of talking about duplicitous, contradictory and ironic signifiers in theory and philosophy, the critic will generally bet with the possibility that no-one-will-understand such complexity and return to and insist on the bonding unity of sincerity. We do have the universities, the resources and globalisation to think otherwise.

I’m in Hong Kong. Every time I go out I see these red busses with ‘sincerity’ and ‘eternity’ written on the back. What am I meant to think? Maybe rather than sincerity being a resistance to alterity, it could be the willingness to attempt to absorb all the possibilities and still have something to say.

A Constructed World (Jacqueline Riva and Geoff Lowe) have been working together since 1993 in a multi-model practice, producing performances, publications, paintings and video works.