Conventionally a retrospective exhibition is taken as an occasion for the artist to present his [sic] work to date as a reified, ‘logical’ whole, and as an opportunity to demonstrate that he has progressed. That one should be offered such an opportunity at all suggests the achievement of a certain currency in art world chit-chat, usually based upon the journalistic acceptance of ‘early work’ rather than upon the significance of current activities. Consenting artists sit Jack Horner-ish in the corners of society, proudly exhibiting mouldy plums.1

— Art & Language

Under the ‘aegis’ of Robert Rooney’s donation of much of his art collection to the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV), Endless Present: Robert Rooney and Conceptual Art 2010 presented a host of conceptual works by artists from Australia and elsewhere, produced in the 1960s and 1970s during the movement’s heyday. This was a decentered exhibition in the very best way. Rooney’s collection of conceptual art and artists’ books — authored by himself and others — served as the exhibition’s ‘fulcrum’, undoing the figurative and the canvas, but also presaging and gently critiquing avant la lettre contemporary art’s post-intermedia world.

Rooney’s cultural gift to the NGV, which formed the backbone of the exhibition, offers a very public way to ‘unpack the library’. Its significance lies in its inferred cumulative weight — the part of the whole seen in Endless Present suggested an almost Matryoshka doll-like collection that continually builds down, folds and unfolds, flips and turns pages, and mirrors itself as it disappears into the creases. There’s space here for infinite referentiality — seen, for example, in the way the blank capture of city streets in Rooney’s War Saving Streets 1970 sat next to Roger Cutforth’s Noon Time-piece (April) 1969; or in the introversion of Mel Ramsden’s Secret Painting 1967–68 in relation to the extroversion of his colleague Ian Burn’s Mirror piece 1967, both dealing with a fundamental removal of the artist’s self from the frame: for Burn, the reflection, for Ramsden, the palimpsest.

The richness and art world cosmopolitanism of the Rooney collection belies the reticent nature of its collector. An early fascination with the work of Ed Ruscha led to a fan letter, which engendered mail and catalogues in response. Sometimes it seems as though a good portion of Rooney’s artistic life has been conducted in print, on print, through the postal service and the printed word; as co-curator Maggie Finch notes, ‘although he never travelled overseas, Rooney has joked that he would have liked to have done a “Grand Tour of Hawthorn”’.2 The artist’s relationship with print takes many forms: the chemical machinations of the photograph (his apparatus of choice through most of the 1970s), his Spon publications, his artist books, his use of cereal (serial) packet shapes for 1960s paintings like Kind-Hearted Kitchen-Garden Nos. 1–4 1967 (whose title incidentally was taken from the top left hand side of a random page of the dictionary and indicates the span of the words on the dictionary page). When taken together, these textual fragments are understood as an indexical referent.

This also resonates through Rooney’s humorous Words and Phrases in Inverted Commas from the Collected Works of IBMR 1972, where he takes the post-structural textual suspensions that dogged the writing of Burn (a.k.a. IB) and Ramsden (a.k.a. MR) and creates a simple list of the infernal inverted commas — a suspension of suspension, if you will. As Gary Catalano explains:

Rooney alphabetically listed their key words and expressions and noted the frequency with which they occur. If the work read like a simple-minded and provincial homage at the time of its compilation, it hardly does so now … ‘cut’, ‘hole’ and ‘mute’ are to be found at the end of their respective letters, and all of them serve to puncture the pretentious jargon of the source text.3

Rooney bolstered the banal. There’s a dry, arched-eyebrow geniality to Rooney’s War Savings Streets 1970 and Holden Park 1 & 2, ‘bonus’ photo version 1970, both of which had Rooney documenting his local area through programmatic photographic works, that’s less about a kind of de Certeauian ‘theory of everyday life’ and more about the capture of mundanity, not to exalt its suburban ordinariness (this eventually led critical practice down the flimsy corridors of cultural studies and endless relativism) but to suggest that the indexical nature of life is inherently writ in the formal repetitions of the manufactured world — the Holden, the weatherboard home, the war savings street, the kerb, the lightpost, the Melbourne city grid. Similarly, the compulsive documentation of periods of Rooney’s life through his culinary experiences, in Meals, Jul–Aug 1970 1970 suggest not a poetics of ordinariness but a mute acceptance that, in the end, the index, the habitual, the ‘strategy’ is all.

—

I went in for my interview for this fantastic job… The job had a great name — I might use it for a painting — ‘Perpetual Inventory’.4

— Robert Rauschenberg

At the beginning of her essay ‘Perpetual Inventory’, Rosalind Krauss describes Brian O’Doherty’s address of the manner in which Rauschenberg ‘defamiliarise[s] perception’, suggesting that, in ‘O’Doherty’s terms, ‘the city dweller’s rapid scan’ would now displace old habits of seeing and ‘the art audience’s stare’ would yield to ‘the vernacular glance’. She continues:

With its voraciousness, its lack of discrimination, its wandering attention, and its equal horror of meaning and of emptiness, this leveling form of perception, he wrote, not only accepts everything — every piece of urban detritus, every homey object, every outré image — into the perceptual situation, but its logic decrees that the magnet for all these elements will be the picture surface, itself now designed as the anti-museum.5

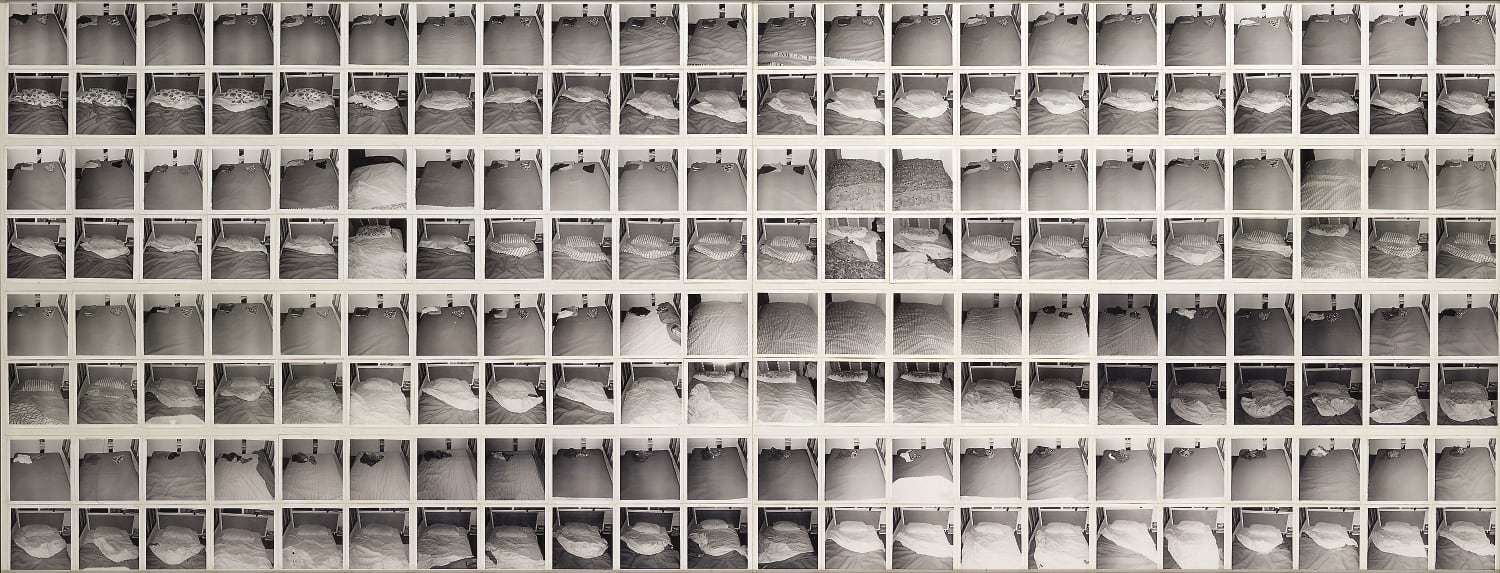

This ‘vernacular glance’ is suggestive of the common-place, unattended observation that resonates through Rooney’s photographic series of the 1970s, from the aforementioned War Savings Streets and Holden Park, through to AM–PM: 2 Dec 1973 – 28 Feb 1974 1973–74, where Rooney ‘ritually’ photographs the head and foot of his bed, morning and evening, over the three months in question. The ambivalence of the blank photographic document suits this: indeed, it was Rooney who described the camera, his tool of choice for over a decade, as a ‘dumb recording device’, which, if nothing else, begs the question of what a ‘smart recording device’ could be. While there are of course semiotic readings possible of all of Rooney’s photographic series — the suburbs, the class divide, the shift in Australian culture from the 1950s to 1960s (and beyond), the materiality of the documented constructs, the cultural weight of the Holden — the repetition in Rooney’s photographs tends to temporarily erase those readings in favour of a kind of hypnotism of the banal.

—

Although Rooney’s programmatic was about erasing the self from his art, his droll, inquisitive personality marks the artist as distinct from his peers, and his endless questing is invested in every document collected in Endless Present. This flags one major difference between now and then. Now, the presentation of the intimate self — through personal fanzines, reflexive performance art, diaristic video works etc. — reflects the quasi-individuation of neoliberalism. This stretches through the writing of perzinesters, through the narcissistic sprawl of the blogworld mediapolis, the self-importance of architectural ‘reflective practice’, the capitulation to capital of the ‘Creative Industries’, home diary via YouTube (and its non-ironic artistic uptake) and on into the complex threads of modern conceptual and performance art borne of such moments as Tracey Emin’s bed and tent works. Rooney’s compulsive slices of life from the 1960s and 1970s perfectly captured the banality of Australian life, through the blank photographer’s eye. From locality to globalisation, the reflective impulse of the artist mirrors the mediated imperatives of the self. For the perzinester’s self-indulgence, consider Rooney’s self-erasure. It’s the very opposite of modern ‘affluenza’, and an art world that’s bent on the logic of the funding tranche.

*Jon Dale writes on music and culture for Dusted, Signal To Noise and Uncut. He also recently wrote on sound artist Tim Coster for ACCA’s New11 catalogue.*