Karaoke Theory

Andy Thomson

Light Projects

12–31 October 2009

Visually sparse, Andy Thompson’s Karaoke Theory saw the gallery at Light Projects almost empty. The sound of a woman singing, however, filled the gallery — her voice emanating from two small speakers on the gallery floor. The lyrics were passages from the writing of Maurice Merleau-Ponty, complete with bibliographic reference to his seminal Phenomenology of Perception. This gesture, in remarkable shorthand, captures one of the central tensions of phenomenology: the space between thought and sense, between cogito and flesh. This is the tension that guides us through Karaoke Theory.

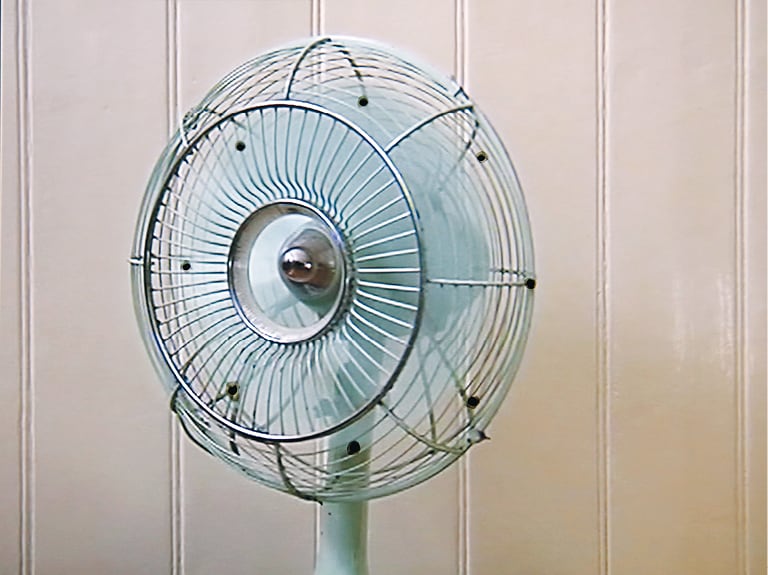

With the windows blackened, Karaoke Theory could not be consumed by the distracted gaze of the passerby. Instead we were invited to enter the space, which remained light-filled via the open door. The dominant visual object in the gallery was a compact data-projector placed on a large centrally positioned plinth, visible before the projected image and forcing the viewer to move further into the space. Total visual absorption in the projected image was clearly not the goal here. The projection did not transport us to another place, but instead led us through the gallery. The projected image depicted a desk fan in motion, its blades turning rapidly. Facing each other, the projector and the image of the desk fan had a cautious equivalence. The faint whir of the projector’s cooling fan provided another slightly off-kilter, though this time aural, signifier of the fan.

The physical presence of the data-projector, emphasised by its placement, is not incidental to the broader concerns here. Standing directly in front of the image of the fan, a slight breeze could be felt escaping through small holes cut into the wall onto which the image was projected. The wall, constructed for the exhibition, presumably concealed a physical fan, possibly even the same fan from the image, and similarly turned towards the viewer, circulating air. Something curious happened when we felt this breeze: because of the placement of the projected image and its source, the viewer could not feel the air blowing through the holes in the wall without casting a shadow and blocking the image of the fan. Initially, this seemed unremarkable. Often when the data projector is used in contemporary art, a part of the experience of the work is the inevitable ‘dance’ around the gallery in the attempt to find a viewing position without casting a shadow. Yet lingering in the space, and letting the elements play off each other, this physical arrangement came to seem not incidental, but instead a central outcome of the work — crucial to its concerns. Through this structure of interaction, the body is forced into the vision. Through their shadow, the viewer becomes acutely aware of their presence in the gallery. Instead of attempting to subtract the body of the spectator from the space, Karaoke Theory emphasises this.

Vision has a particular place in the constitution of phenomenology. Throughout the history of philosophy, it is the eye, more than any other sense, which has been seen to have an affinity with thought. The metaphorical analytic vision and the physical ocular phenomenon of vision, are entangled beyond resolution. Karaoke Theory resists the disembodying impulses of vision via both the physical position of the data projector and the concealed fan. Touch and sight are not reconciled here; it is not possible to experience the touch of the fan and keep it in full sight. Yet neither are these senses easily separable in the viewer’s experience of the fan. The tension is not resolved, just as phenomenology has never settled the relation of thought and sense. As concluded by Stephen Palmer in his eloquent and thoughtful catalogue essay, Karaoke Theory is a proposal of a set of relations, not a solution. Resolutely, though, Karaoke Theory does inscribe the space of the projected image in the gallery as a space of the body.

A round table discussion published in October identified the ‘virtual’ and the ‘phenomenological’ as opposing tendencies in the use of the projected image in contemporary art. Considered dominant, the virtual is centered on pictorialism and invites the viewer to embrace the virtual elsewhere of the image, while the phenomenological emphasises architectural space and the materiality of the image.1 Karaoke Theory clearly positions itself in the latter camp, and Light Projects has become a fascinating space in this regard, with their exhibitions often offering an active engagement with the peculiarities of the space.2 The phenomenological approach to the projected image has become particularly embroiled in the almost fetishistic use of 8mm and 16mm formats in contemporary art, with their large and noisy physical presence, and visible materiality in the degradation of the film stock. However, the digital image has its own object status within the gallery, and Karaoke Theory offers a memorable and engaging consideration of this.