Jenny Holzer ACCA, Melbourne 17 December 2009 – 28 February 2010

The question of how art can respond to the politics of war hangs like a guilty cross about the neck of contemporary art. With an eye to the — often art-fuelled — activism of the Vietnam war era, there is a growing sense that today’s wars are marked by a failure of protest, a failure felt perhaps most keenly by the worldwide multitude that marched on 26 February 2003 in opposition to a war that began in Iraq only a few days later. This question of art’s role in the politics of war was raised in a recent exhibition at the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, by the work of the contemporary US artist, Jenny Holzer. Featuring two of Holzer’s more important recent works — a selection from the artist’s 2006 series Redaction Paintings, and a specially created interior light projection — the show revealed an engagement with the politics of war that was at once powerful and complex, but ultimately flawed.

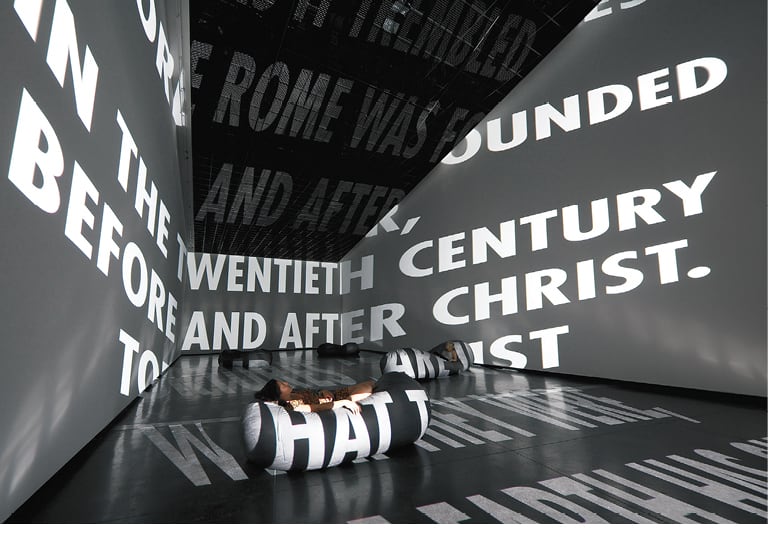

The first work in the exhibition was the interior light projection, For ACCA (2009). In this work, with the aid of an industrial-sized projector, the words of Polish poet Wislawa Szymborska were scrolled across the floor, walls and ceiling of the darkened gallery. Viewers could hover in the doorway of the gallery or watch from beanbags, which had been fabricated from a heat-sensitive material that created darkened stains where it contacted the warm bodies of its occupants. For ACCA is the most recent in a series of projections that Holzer has installed in places all across the world, from the Jüdisches Museum in Berlin, to waves and mountains in Rio de Janeiro. In these previous iterations, the projections have succeeded by spectacularly intertwining word and place, drawing out and questioning the political and historical resonances of the sites in which they are shown. The ACCA work, however, was empty of such resonances, and the blank walls of the contemporary art kunsthalle remained just that: blank. This is not to say that the ACCA site is without history — it is, like the rest of Melbourne, a colonised space — but Holzer’s work failed to engage with that history. More fundamentally, however, For ACCA did not work logistically. The projection felt crowded and awkward. The words contracted and expanded frustratingly across the walls and ceiling, making Szymborska’s beautiful poems all but illegible, while the beanbags appeared like kitsch lounge room accessories.

The Redaction Paintings, in contrast to the obscurity of the projection, were startling in their clarity. The twelve works — selected from a series of 32 works — comprised large under-painted canvasses, onto which Holzer had screen-printed documents obtained from the US government under Freedom of Information laws. The documents revealed disturbing details concerning the treatment of prisoners by US troops in Iraq. There was a ‘wish list’ of ‘alternative interrogation techniques’ — the discomfort of ‘close quarter confinement’, explained one document, induces compliance and cooperation — and a series of statements by Iraqi prisoners revealing their abuse by coalition forces.

The works were as much about revealment as about concealment. Most of the documents used in the show had been heavily redacted by government officials to conceal the personal details of the Iraqi prisoners and coalition soldiers they concerned. On canvas, these redactions amount to almost abstract brushstrokes, dramatising the sinister intent that belies the cold objectivity of the documents. This ambivalence towards Iraqi bodies as both means to an end, and as subjects of a targeted elimination, was also played out through the layers of the canvasses themselves, between the mass-produced repetition of the screen-prints and the expressive colour-fields of the underpainting. In this sense, the works tied off an art-historical arc that included the tough politics of 1970s feminism, the language-based conceptualism of Barbara Kruger and finally the glib factory-line death of Warhol’s Death and Disaster series. These were indeed intense and complex works.

Yet, for all this, these works felt flat and lifeless. Why is this? In her previous works — such as her famous -Truisms (1977–79) — Holzer used words to highlight the ambiguity of language and ideology, a technique which empowered viewers to question the authority of these forces to shape and frame their lives. The directness of the Redaction Paintings, however, allows no such empowerment. In the documents Holzer reproduces, the lives and bodies of Iraqi prisoners are framed by the bureaucracy of war as expendable, without value. While Holzer’s canvases dramatise and critique this framing, they cannot, in the end, escape it, and this is their failing. As the theorist Judith Butler has so eloquently articulated, before we can begin to grieve the lives of those destroyed or tortured by war, we must first conceive of those lives through a frame that gives them value, that renders them ‘grievable’.1 It is not a matter of counting the dead, but of counting the worth of the lives that have been lost. We cannot truly cry out at the injustice perpetrated against the lives framed in Holzer’s -Redaction Paintings, because they are not lives in the truest sense. The Redaction Paintings fail to properly grieve lives lost and tortured because, in Szymborska’s words, ‘they forget what’s here isn’t life’.2

Holzer’s failure on this point inhabited the entire show. In light of the lifeless bodies that inhabited the Redaction Paintings, the impracticalities of the projection work also took on a sinister hue — the obscurity of the poems became the obscurity of denial and redaction and the kitsch beanbags became bodybags. In turn, the light projection undermined the complexity of the Redaction Paintings, encouraging us to view the large canvases’ critique of bodily violence as yet another spectacle. Shown together, these two very different works drew out the worst in each other.

Seven years after the US-led invasion of Iraq, and four years after the revelation of torture by US troops in Iraq’s Abu Ghraib prison, an end of sorts now seems imminent — Australian troops returned home in July 2009 and, as part of Barak Obama’s ‘responsible withdrawal’ plan, US troops are due to reduce by half in August this year, with a full withdrawal scheduled for December 2011. At its best, contemporary art might help us to envisage how this withdrawal could really be ‘responsible’. It might help us to frame the lives of those affected by the US presence in Iraq as inherently valuable, and thus ‘grievable’, i.e., in terms other than those of the soon-to-depart bureaucracy of war. The works by Holzer shown at ACCA failed to achieve this, not only on logistical grounds — the crowded and illegible projection — but also on symbolic and political grounds. The Redaction Paintings undoubtedly offered a complex and powerful indictment of war and its atrocities, but the lifelessness of these works signalled that indictment is no longer enough.